Sky People Statement (2009 - 2020)

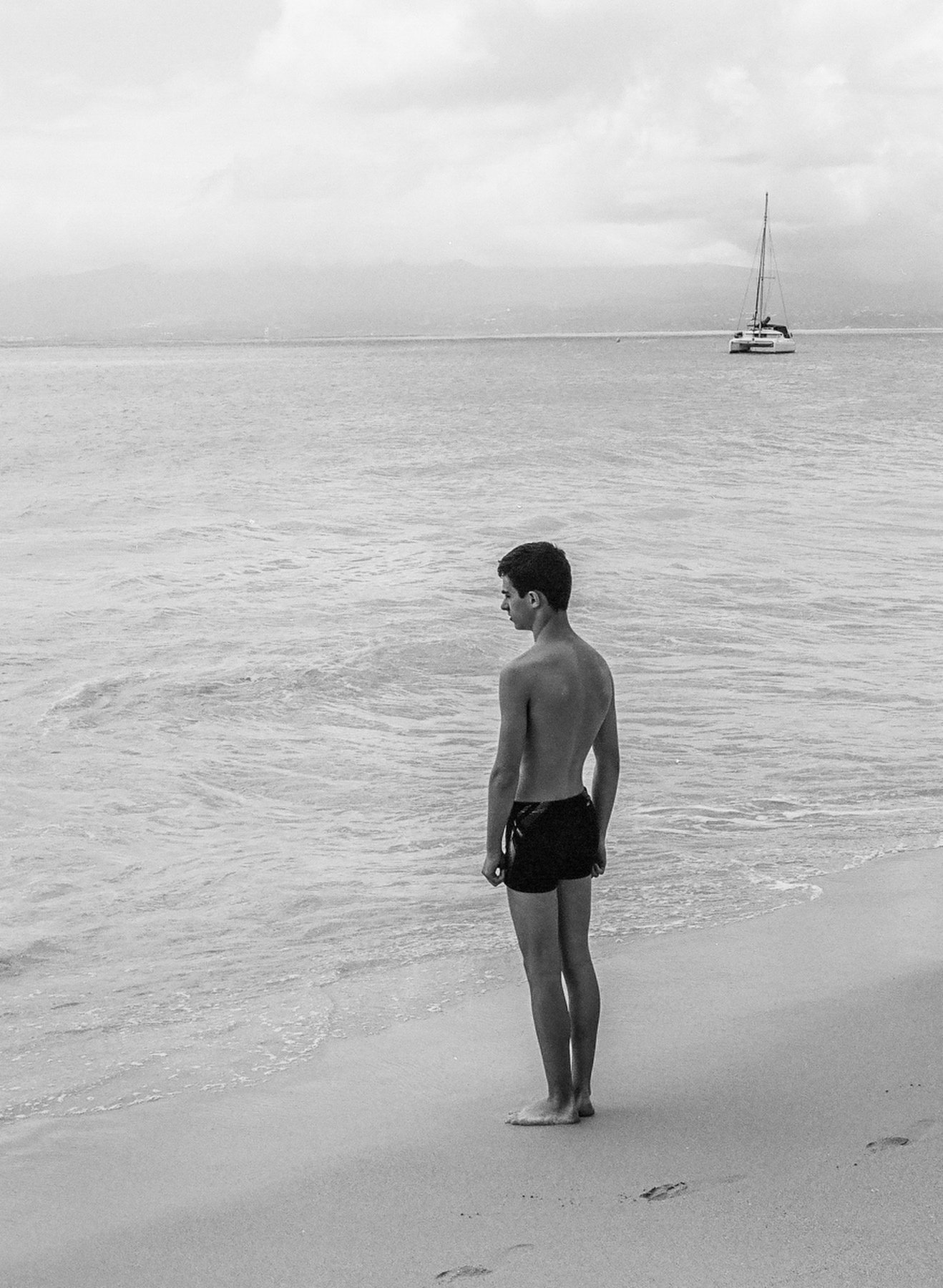

According to their notebooks, when Italian explorer Cristobal Colón and his Spanish fleet of three ships arrived in the West Indies in 1492, the indigenous islanders thought that the explorers must be gods. They called them Sky People. The native Taíno people soon found the newcomers to be diseased, greedy, and power hungry people willing to stop at nothing to satisfy their desires and spread their worldview and religion. This moment in history set into motion a chain of events that largely shapes our existence to this day.

One of the most direct manifestations of this lineage of colonialism involves much bigger ships arriving daily to these same islands and the far reaching cultural and economic impact of the cruise industry. In retrospect, the morality and sense of right and wrong feels pretty straightforward when looking at the years following first European contact. The enslavement of native populations, followed by slavery of Africans when too many of the natives died off from war and disease, is undeniably evil. The current dynamics surrounding tourism economy and cruises in particular are much more morally complex. My twelve years of cruising for this project have been driven by a deep sense of discomfort in the types of interactions that I see. Any cultural exchange predicated on commerce feels sticky, but at cruise ports that would be an understatement. However, I have found very few cruisers or local islanders who are vocally discontented with the arrangement. Most locals tell me they are grateful for the tourism based economy. This, however, brings us to a very important piece to keep in mind. Who am I?

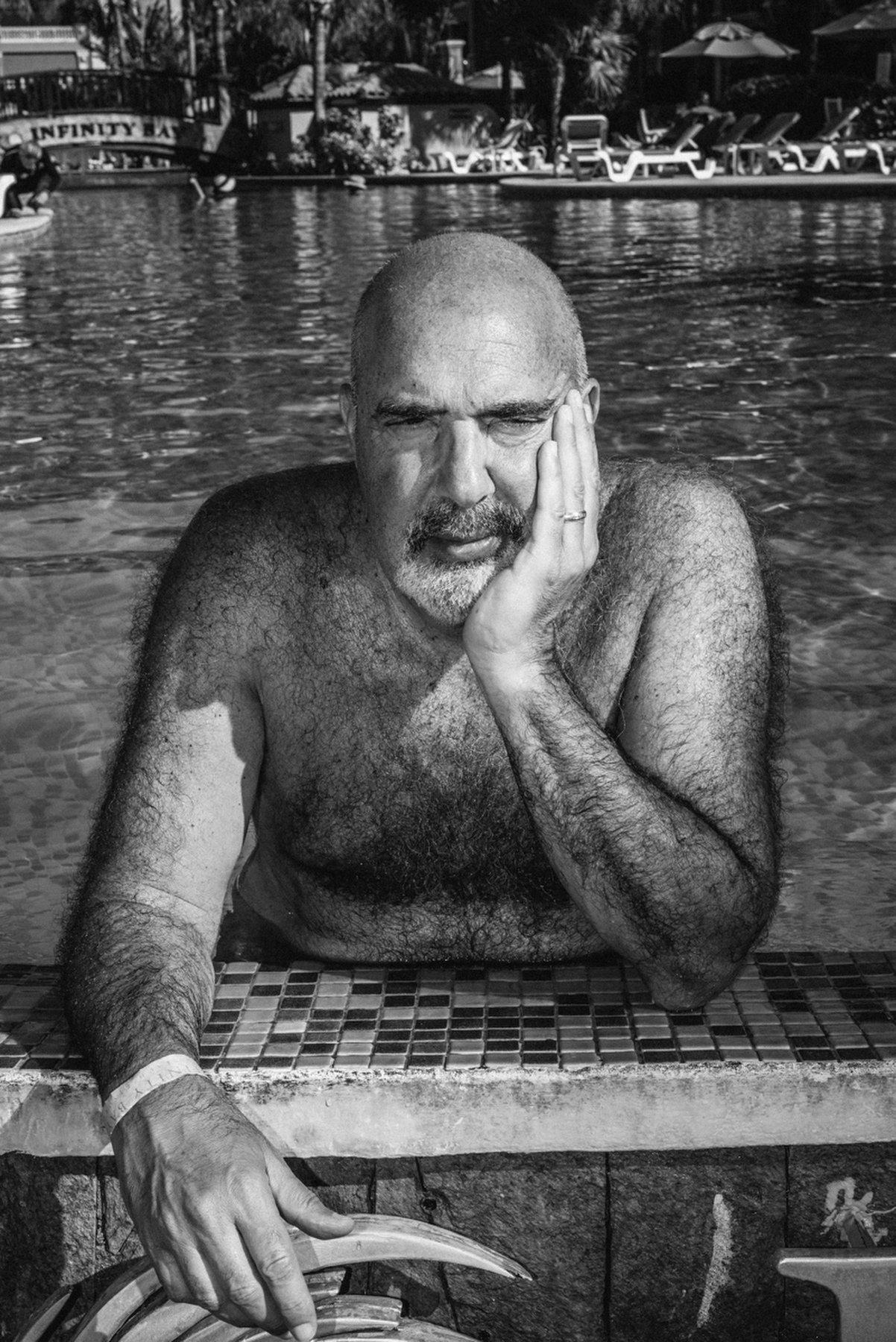

There are some things that are important to know about me for the purposes of this project. Although I think of myself as vastly removed from the “cruiser” in this equation, I am, in fact, a cruiser. In every interaction I’m having with either locals or cruisers, I’m seen as a cruiser and that is informing the interaction. Secondly, I’m white. More specifically, my family lineage goes back to the same country of origin as Colón himself. Also sharing that lineage is the cruise lines themselves. Ten of my eleven cruises over the last 12 years have been on Costa or MSC cruise lines, both of which are based in Geneva, the very city where Colón was born. Implicating myself in this lineage is a tough pill to swallow, but central to the work. This is a project about the white/European gaze through a context of history and colonialism as seen through the modern cruise industry, as seen through the lens of a white American of Italian descent.

Cruises are chosen as a form of vacation by so many for two main reasons — they are relatively cheap as international vacations go, and, crucially, they are easy. You don’t have to think about anything, and everything is brought to you. I disagree with the premise that cruises are mentally easy. I find cruises to be one of the most mentally taxing experiences I’ve had, which is why I’ve had to keep coming back for years to dig deeper into my own understanding and interpretation of what I’ve seen.

A simple examination of why they are cheap and easy paints a picture of the moral complexity. They are cheap because the cruise companies are able to exploit the relative poverty of the port countries and countries such as the Philippines and Indonesia where they source their staff. Cruises are easy because these workers don’t have the power to demand better working conditions and are forced to work intensely long hours catering to every need of every cruiser.

These power dynamics and the resulting leverage are seen at every scale on the ships and at port. The racial breakdown of these dynamics are stark and unarguable. Walking into a dining room on a cruise ship, it’s hard not to notice that almost every person sitting down is white and very nearly every person serving the diners are people of color. On the Caribbean ports the racial division between white cruisers and black or Latin American locals is equally stark.

This isn’t intended to be the whole story; take it with a grain of salt, or challenge my telling. This is not a documentary. I am not telling the story of someone else’s life experience; rather, it’s an internal journey that involves and implicates others.