Cherokee for The New York Times

When I started visiting The Qualla Boundary (the home of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians) in early 2020, photography was the farthest thing from my mind. As a plant enthusiast and a homesteader, I was drawn to the wisdom, knowledge, and perspectives that were truly new to me about how to be in right relationship with the land both in the woods, and in the garden.

As a life long wild foods enthusiast, I was amazed to hear my new friends Tyson, and Auntie Amy talk about their staple food plants, most of which I had never even heard of. This was astounding to me, becuase I’ve gone on countless wild food walks with dozens of local experts and thought I knew basically all of the wild foods this region had to offer. I was immediately humbled by how much I still had to learn.

Auntie Amy’s garden sits in a low lying valley known to the Cherokee as the Kituwah Mother Village. Kituwah is the site of the original epicenter of the entire Cherokee nation. A mound marks the site where many chiefs have been buried over the years, but throughout the valley, the bones of the ancestors rest in the rich soil where Amy Walker and others grow their food.

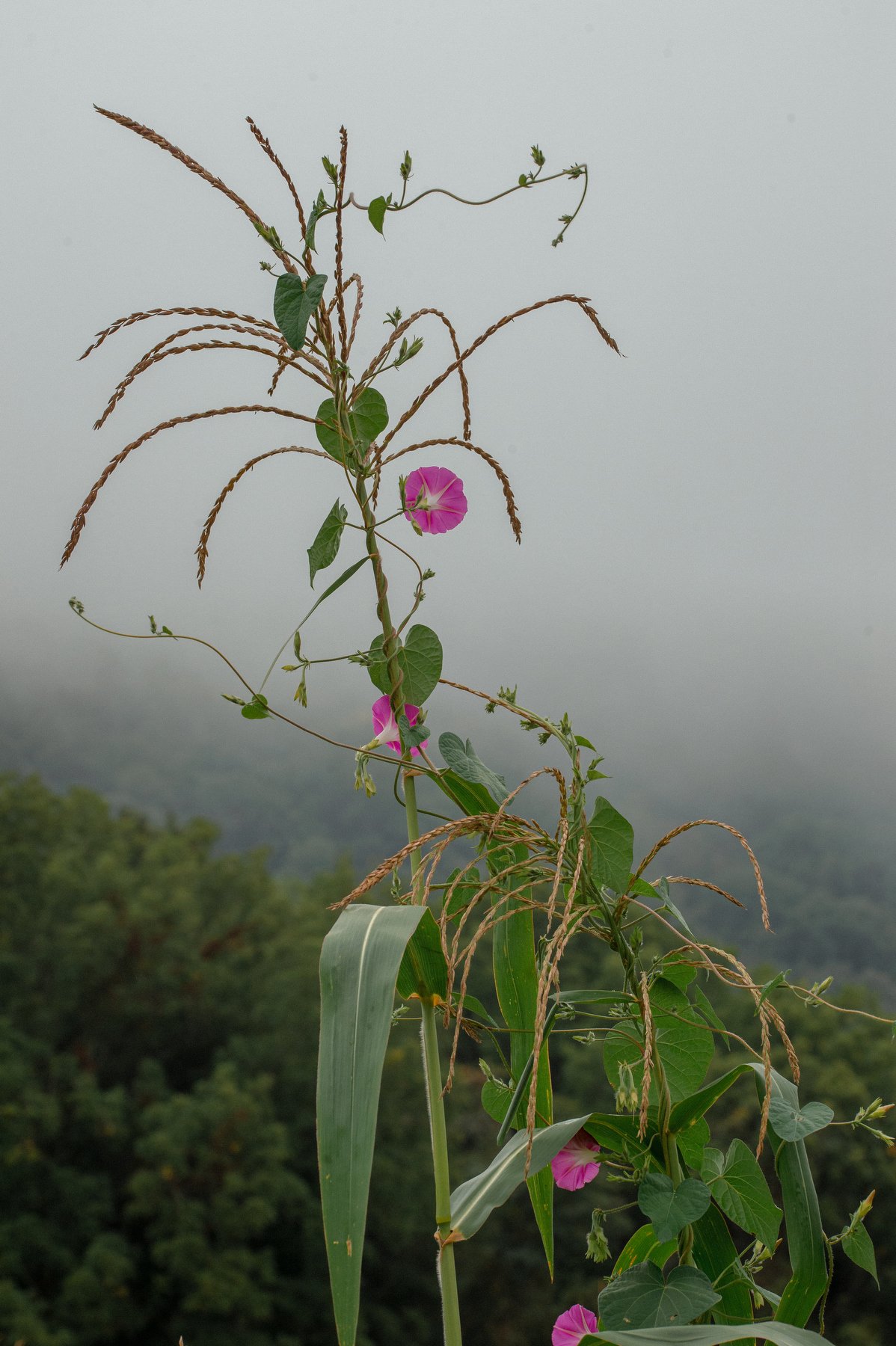

To truly understand the meaning of connection, one must spend time with indigenous people on their original land. In Cherokee the traditional foods are a vital way to keep culture alive. A typical meal at Tyson’s Sampson’s house will include heirloom varieties of corn, beans and squash that have been passed on generation to generation, grown in this hallowed soil with so much cultural significance, as well as mushrooms, greens and herbs from the surrounding hills. The knowledge needed to gather food from the woods is also passed on generationally, as folks like Tyson, often pick from the same ramp patches that they first picked from as a child with their grandmother. The processing of the wild and cultivated foods is another way of communing and passing knowledge down. Countless hours are spent cracking black walnut shells, grinding corn, or canning poke salat.

The enormous garden and the vast surrounding woods supply a great abundance which produces a gift economy that subverts capitalist systems more than anywhere I’ve ever been. Everything is given freely and there is a true balance and reciprocity that exists. When true reciprocity exists that benefits everyone equally, the lines between giving and receiving get blurred. In giving to your family and community you are receiving something. By receiving you are giving. For example, for Tyson to receive the wisdom that Amy shares, to carry on her garden once she is no longer able (hard to imagine as she out works everyone else there at 82), to continue to plant the same corn and bean seeds, and so on. It’s the ultimate gift to her and all she could ever ask for. By receiving he is giving.

My eventual decision to bring photography into the equation was a way for me to have something to give. I wanted to make my images available for my friends on the Qualla Boundary to help promote the important work that they are doing through the Big Witch Indian Wisdom Initiative. I partnered with The New York Times in order to help spread the word about this community in a story that published in October of 2023.